The Hector ‘passenger list’

When you find a passenger list containing the name of your ancestor you strike genealogical gold. And on the internet you can readily find a list of 40 or so ancestral passengers on a 1637 voyage of the Hector to Boston—John Brockett, for example, is on the list. But all that glitters is not gold, and what you can’t find is documentary evidence of that list. To be blunt, an original list of those 40 or so passengers for that voyage of the Hector in 1637 doesn’t exist. It’s what’s called a factoid. The dictionary definition of a factoid is “an assumption or speculation that is reported and repeated so often that it becomes accepted as fact”, and the passenger list of the 1637 voyage of the Hector is an example of one. This webpage suggests how the tale first emerged and how it grew in the telling. If you don’t have the time to read the discussion in full you can find a summary of the 6 main stages in the development of the tale by clicking+Read more

1. 1637: Winthrop’s contemporary report that 5 men arrived on the Hector and another ship in Boston 26 Jun 1637.

2. 1902: Atwater’s ‘company’ of emigrants that chartered the Hector. He named some of them, but doubted that a passenger list would ever be discovered.

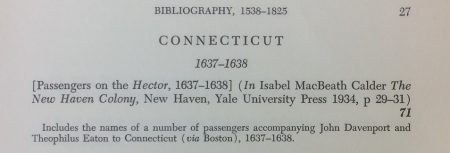

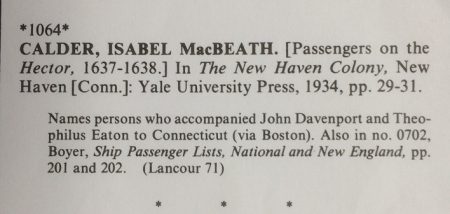

3. 1934: Calder’s ‘group’ of emigrants that chartered the Hector. She listed 48 passengers, but didn’t refer to a passenger list as such.

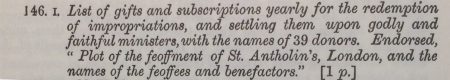

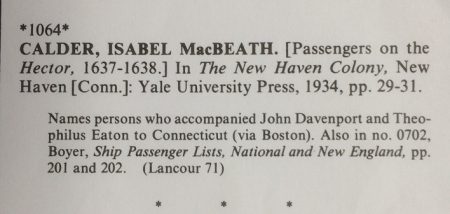

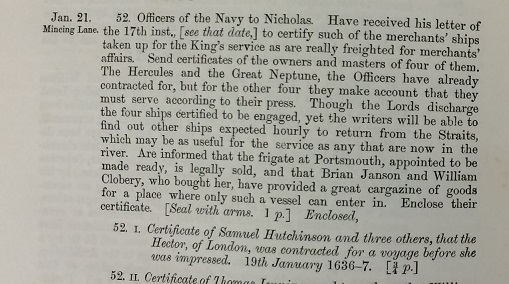

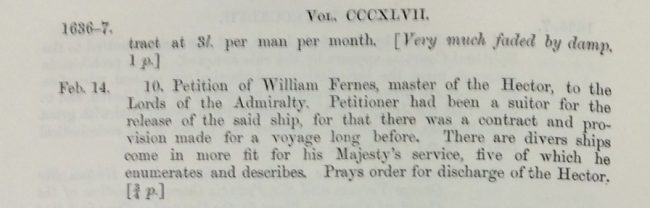

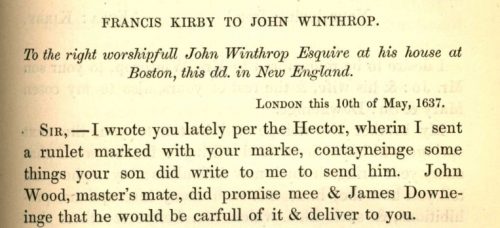

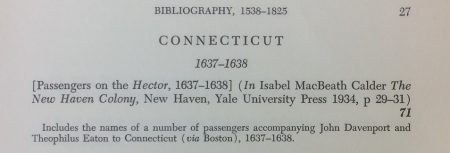

4. 1938: Lancour’s item 71 in his Passenger Lists of Ships cited Calder p 29-31 as the source for “[Passengers on the Hector, 1637-1638]”, implying an actual passenger list. For an image of item 71 see below.

5. 1977-80: Boyer’s Ship Passenger Lists and Filby’s Passenger and Immigration Lists Bibliography 1538-1900 recited Lancour’s reference to Calder’s work as “[Passengers on the Hector, 1637-1638]”.

6. Today: A transcription of an alleged passenger list with 40 or so names is readily available on the internet, usually citing Lancour, Boyer, and/or Filby (who all cited Calder).

For some comments on this webpage, see the separate page

Comments you’ve sent. If you notice anything inaccurate or unclear in this discussion, do please email us at

broket @ one-name . org (spaces inserted to reduce spam).

A summary was published in the winter 2021 issue of American Ancestors magazine, pp 36-39, published by New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston MA, entitled: Deconstructing the

Hector “Passenger List”, author: A A Brockett.

1. Before 1902

Only one list of passengers on the 1637 voyage of the Hector and the other ship has so far been found that dates from before 1902. It wasn’t a ‘passenger list’ in the sense of a formal document drawn up by the officer of a ship or of a port of departure or arrival, but was the mention of 5 men on board in Winthrop’s journal entry recording the ships’ arrival in Boston 26 Jun 1637. It is contemporary, valid evidence:+Read more

[1637 June] 26. There arrived two ships from London the Hector, and the [blank]. In these came Mr. Davenport and another minister, and Mr. Eaton and Mr. Hopkins, two merchants of London, men of fair estate and of great esteem for religion, and wisdom in outward affairs.

+++

In the Hector came also the Lord Ley, son and heir of the Earl of Marlborough, being about nineteen years of age, who [p 224] came only to see the country. He was of very sober carriage, and showed much wisdom and moderation in his lowly and familiar carriage, especially in the ship, where he was much disrespected and unworthily used by the master, one Ferne, and some of the passengers; yet he bare it meekly and silently. When he came on shore the governor was from home, and he took up his lodging at the common inn. When the governor returned, he presently came to his house. The governor offered him lodging, etc., but he refused, saying, that he came not to be troublesome to any, and the house where he was, was so well governed, that he could be as private there as elsewhere.

To summarize, the journal entry said that there were 2 ships, the

Hector and another, and in them came

5 men: Mr Davenport, a second unnamed minister, Mr Eaton, Mr Hopkins and Lord Ley. It mentioned that Lord Ley was treated with disrespect by the master, Ferne, and some of the passengers. Whether or not these disrespecting passengers were among the 4 he had named is left unstated.

If there had been other passengers, Winthrop neither named them nor said how many. Another contemporary document concerning the

Hector prior to its sailing—a Petition submitted in January 1637—mentioned that the freighters had prepared all their provisions and passengers for the voyage, but

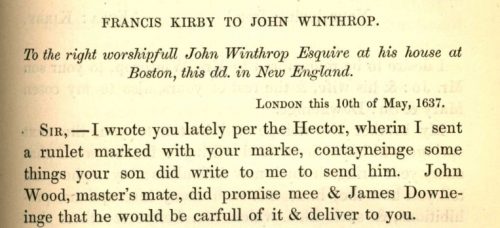

also neither named them nor said how many. Of course, in addition to passengers the ship’s crew was also on the journey and two of them are named in the documents—the Master William Ferne or Fernes, and the Master’s Mate John Wood

—but we don’t include them here in the list of passengers.

The contemporary evidence is therefore only definite about 5 passengers. In the absence of evidence that there were other passengers who weren’t mentioned, we should assume there weren’t any.

Fast forward 180 years and Trumbull apparently only mentioned the ship once, in passing—“the Hector of forty guns”—in his 1818 account of the 1745 siege of Louisburg, and mentioned no passengers. In any case, that 1745 vessel was probably different from the 1637 Hector, as was the one that transported Scottish settlers to Nova Scotia in 1773, a replica of which is now at Heritage Quay on the Pictou waterfront, Nova Scotia. Then in 1874 when Hotten published his book of original lists of emigrants from Britain to the American Plantations 1600-1700 he didn’t mention the Hector.

2. 1902: Atwater’s History of the Colony of New Haven

The next list of passengers on the 1637 voyage of the Hector found so far was in Atwater’s book of 1902, some 265 years after Winthrop’s list. It appears that Atwater was the first to suggest in writing that the Hector definitely brought more than just those 5 passengers across. But his list of names is supported by neither contemporary nor valid evidence, as we explain below.

Atwater devoted a whole chapter in his book to “The Voyage of the Hector” and set the scene for it in the preceding chapter. But he discovered no actual passenger list, and was doubtful one ever would be:

“If ever lists of the passengers in the Hector and her consort should be discovered …”

+++

“No documents have yet been found which indicate the day when the Hector and her consort sailed from London, or the manner in which the officers of the port discharged their official duty in examining the certificates of the passengers.”

2.1. Imaginative narrative

Atwater used a narrative style of writing history, which aimed to tell an imaginative and readable story. This was common among historians at the time—and is today too among historical novelists, although not so much among academic historians. Atwater acknowledged that imagination was necessary regarding the Hector:

“None of the passengers in the Hector, or in the vessel which accompanied her, having supplied us with his journal, we must avail ourselves of diaries of contemporary voyages if we would see them in imagination pursuing their way down the Thames, through the Channel, and over the Atlantic.”

and he proceeded at some length to conclude his chapter about the voyage of the Hector with vivid and dramatic tales of cross-Atlantic sailings by other ships as though they were the Hector.

An effect of this imaginative narrative style is to make it difficult for the reader—and perhaps even the writer—to distinguish fact from fiction. This is not to say that Atwater’s narrative was entirely fictional. He gathered facts from various sources and interpreted them by including them into a larger imaginative story. He—or perhaps co-researchers—sourced and transcribed original documents, and thus did a great service to later researchers. But like everyone Atwater had his own presuppositions and motivations, and regarding the Hector some would probably have been religious, others perhaps genealogical or simply a product of his day and age. When you construct a narrative history of your homeland referring to original documents you naturally try to make them fit with what your world view or philosophy of life lead you to imagine what took place. And it is the way in which Atwater’s own vision of past events imposed a framework on his presentation of the documentary evidence that later researchers need to try and recognize.

The mainstay of this framework upon which Atwater fashioned his narrative concerning the voyage of the Hector appears to have consisted of 2 imaginative—or imaginary—constructs that were mutually interdependent: the ‘company’ and its ‘chartering’ of the vessel. Intimately bound up with these 2 constructs was a 3rd element in the framework: a Jan 1637 Petition. This was not imaginary; it’s a document that survives today, and you can see an image of it below. However, Atwater’s interpretation of it was imaginative, indeed incorrect.

These 3 structural elements fashioned his presentation of the details of his narrative so completely that it can be difficult to see behind the finished facade. However, if we are to understand the later emergence of a ‘passenger list’ we have to try to unveil them. This is because these same 3 elements also provided the underlying structure of the picture painted by Atwater’s successor, Calder, who was the immediate precursor of an alleged actual passenger list for the Hector. She too wrote in an imaginative narrative style, and could be more imaginative.+Read more

For example, she claimed knowledge of the thoughts of someone in the 1630s: “to John Davenport the Congregationalism of Massachusetts Bay seemed no radical innovation but the logical outcome of all his previous experiences.”

But to be clear, calling these constructs of Atwater and Calder imaginative or imaginary is not to say that Davenport didn’t have followers in London. There’s good evidence that for a period he was the vicar of a church there with a congregation. Nor is it to say categorically that none of the people Atwater and Calder listed came to Boston with him and Eaton on the 1637 voyage of the Hector or the other ship. It’s possible, but apart from the 3 mentioned by Winthrop we can’t be sure if any of them did or didn’t. However, it is to say that neither Atwater, Calder, nor apparently any other source, have provided valid evidence that their ‘company’ or ‘group’ existed and acted as they said it did, or included any of the members they listed. And for this particular discussion that means that the alleged passenger list is based on invalid constructs. And in what follows we try to demonstrate this.

2.2. The ‘company’

Without unnecessarily criticising Atwater, whose account of the later colony seems to have been well-researched, one of the two major imaginative features of his narrative about the Hector—later to be developed further by Calder—was his way of asserting that she brought more than 5 passengers to Boston in 1637. This was Atwater’s construct of the ‘company’. He used it in two main senses:

- A collection of people that a leader gathered around him, with reference in this context to emigrants; once using the synonym ‘association’.

- A legal entity, like one that had trustees, or feoffees, and purchased impropriations, or—using a synonym—a ‘joint-stock association’.

2.2.1. 9 examples of Atwater’s usage of ‘company’

The following 9 examples of both usages from Atwater’s narrative should suffice—a search for ‘company’ in the online version will show you others if you are interested. We cite them here in order of their occurrence in his book, highlighting relevant words. In several of the later examples you can see how he blurred the distinction between the two usages:+Read more

Example 1. “The first company who left their homes in the mother-country to establish a Puritan plantation in New England sailed in 1628, and, under the leadership of Endicott, established themselves in Salem. They had been twice re-enforced, when a much larger company came with Winthrop in 1630, and settled first at Charlestown, and afterward at Boston.”

Note: This is an example of Atwater’s 1st usage.

+++

Example 2. “About one year after Davenport had escaped from this danger. Laud discovered the existence of a company, whose design was to purchase such advowsons as, having been impropriated to laymen in the time of Henry the Eighth, were now for sale, in order that the trustees, or, as they were styled, feoffees of the company might present for induction men whom they regarded as orthodox, that is, as Calvinists. The company had been in operation for some years, and had already purchased several impropriations with money contributed for that purpose. The discovery of the project excited Laud vehemently. He hated Calvinists, whether conforming or non-conforming; partly for their theology, and partly for their almost invariable adhesion to the popular side in the contest between the Commons and the king. It was part of his plan of administration to exclude them from preferment; so that this company was, in his estimation, an organized attempt to frustrate his plans. Davenport was one of the feoffees of this company“.

Note: This is an example of Atwater’s 2nd usage.

+++

Example 3. “If for a time he [Davenport] cherished the thought of finding a home in Holland, he had doubtless relinquished it as early as 1635, for in that year his family returned to England. He followed them, probably in the summer or autumn of 1636; for the organization of a company of emigrants was so far forwarded in January of the following year that they had chartered a vessel, ‘made ready all their provisions and passengers, fitting both for the said voyage and plantation, and most of them thereupon engaged their whole estates.'”

Note: This is a crucial example of Atwater’s 1st usage: it was the first time he used the construct with respect to Davenport’s ‘company’ of emigrants. However, it contained connotations of the legal 2nd usage in that he said the company chartered a vessel, as also in example 9 below. So the distinction between the two usages was blurred here. He footnoted his evidence as the Jan 1637 Petition, but it isn’t valid evidence for these assertions (see below).

+++

Example 4. “Besides these who were related to Davenport, as his former parishioners, or to Theophilus Eaton by family ties, Several citizens of London joined the company. Not all of them can now be distinguished from those who came from other parts of the kingdom, but there is more or less authority for including in such a list the names of Stephen Goodyear, Richard Malbon, Thomas Gregson, William Peck, Robert Newman, Francis Newman, and Ezekiel Cheever.

+++The London men with their families forming the nucleus of the company, other families or companies from the rural counties became united with it. One group of families came from Kent …”

Note: This is a clear example of Atwater’s 1st usage. Not only did he here actually name members of the ‘company’—albeit cautiously—but he also introduced the concept of a nucleus within the larger ‘company’, adopted later by Calder.

+++

Example 5. “It was a great undertaking for the company which gradually gathered around Davenport and the Eatons, to prepare for a voyage across the Atlantic, and a permanent residence in the New World. The ministers could perhaps embark, with their books and household-stuff, in a few days; but merchants engaged in foreign commerce needed several months, after deciding to emigrate, for the conversion of their capital into money, or into merchandise suitable for the adventure in which they were engaging.”

Note: This is another example of Atwater’s 1st usage containing connotations of the legal 2nd usage. The ‘company’ here was the emigrants preparing for a voyage but also among their number were merchants engaged in foreign commerce.

+++

Example 6. “Another company came from Hereford, a shire in the West of England, bordering on Wales. The particular events which moved them to leave their homes at that time are yet to seek; but it is known that they left under the influence and guidance of Peter Prudden, a clergyman of Hereford, well known to all of them by reputation, if not by personal knowledge of him as a preacher and pastor. Probably they learned through him of the expedition originated by Davenport and his friends, and became, through his agency, members of the association which, leaving London in April, 1637, founded New Haven in April, 1638.”

Note: This is again an example of Atwater’s 1st usage with connotations of the 2nd usage. He was using the word ‘company’ to refer to a similar group of emigrants who joined Davenport’s company of emigrants whom he called here ‘the association’, with its legal connotations.

+++

Example 7. “But this company projected something, more than emigration. They were not to scatter themselves, when they disembarked, among the different settlements already established in New England, but to remain together, and lay the foundation of a new and isolated community. For this reason a more comprehensive outfit was necessary than if they had expected to become incorporated, individually or collectively, in communities already planted. In addition to the stores shipped by individuals, there must be many things provided for the common good, by persons acting in behalf of the whole company. There is evidence, that, after the expedition arrived at New Haven, its affairs were managed like those of a joint-stock association, and therefore some ground for believing, that, from the beginning, those who agreed to emigrate in this company, or at least some of them, associated themselves together as partners in the profit and loss of the adventure.”

Note: This is an example of Atwater clearly combining both 1st and 2nd usages with reference to the emigrants after they had arrived in New Haven.

+++

Example 8. “If the ship was chartered by a joint-stock association, it does not follow that the shareholders took passage in her. The Massachusetts Bay Company had a regular tariff of rates at which they received all freight that was offered, and all passengers who were approved. Theophilus Eaton owned a sixteenth of the Arbella, which had been purchased expressly for that company‘s service; and both he and Davenport, as directors of the company, had become familiar with its methods. The rates of that company were five pounds for the passage of an adult, and four pounds for a ton of goods. The association of adventurers which chartered the Hector would naturally adopt similar methods and similar rates. …”

Note: This is another clear example of Atwater’s 2nd usage, and a way of explaining that his ‘company’ that allegedly sailed was the 1st usage.

+++

Example 9. “Before the Hector sailed, the company which chartered her had so increased that it became necessary to hire another vessel to accompany her on the voyage …”

Note: The surrounding context shows this to be primarily an example of Atwater’s 1st usage, but like example 3 it had connotations of the legal 2nd usage in chartering a vessel.

2.2.2. Names of members

A natural corollary to constructing a ‘company’ in England was to name some of its members. In addition to Davenport’s wife Atwater named various relatives of Theophilus Eaton, plus suggesting that several citizens of London joined the company. “Not all of them can now be distinguished from those who came from other parts of the kingdom,” he acknowledged, “but there is more or less authority for including in such a list the names of Stephen Goodyear, Richard Malbon, Thomas Gregson, William Peck, Robert Newman, Francis Newman, and Ezekiel Cheever.” But he didn’t cite his authority, neither more nor less. Calder later named some of these men in her lists of names, but not all of them. She didn’t cite authorities either, see below.

2.3. ‘Chartering’ a vessel

Intimately linked, or twinned, with his construct of the ‘company’ Atwater introduced the concept of them ‘chartering’ the Hector. This was the other major imaginative construct that shaped his narrative. And it’s necessary to unravel it, because once again Calder followed him and used the same concept, and from there it fed into to the notion of a passenger list. For the meaning of ‘chartering’ a vessel+Read more

The verb is obviously the action relating to a ‘charter’, which is an ancient legal term for a written instrument or contract. Not that the meaning had changed greatly over the centuries, but it’s Atwater’s use of the term that we need to understand since he was a late 19th C, early 20th C American. The relevant definition in the NSOED is no.3 dating from the late 18th C “Hire (a ship, vehicle, aircraft, etc.) as a conveyance.” The online Mirriam-Webster doesn’t give dates but its relevant definition is no.2 “to hire, rent, or lease for usually exclusive and temporary use” with the example “chartered a boat for deep-sea fishing“. Mirriam-Webster‘s definitions of the noun all concern legal contracts, and its 5th definition is pertinent to cite here: “a mercantile lease of a ship or some principal part of it” with the example “In the charter the ship’s owner agreed to transport specified cargo to a specified port.”

+++

These Dictionary definitions are clear that chartering something, especially as large as an ocean-going vessel or an aircraft, isn’t the kind of simple hiring you do when you hire a taxi, but is the drawing up of a formal legal contract between parties, with considerations, signatories, etc. and is then followed by extensive preparations like recruiting crew, arranging docking, gathering export goods, negotiating passengers, etc., etc. Chartering a cross-Atlantic vessel would typically involve freighters, experienced at making such journeys, drawing up and agreeing a contract with owners who had invested capital to build and fit out a vessel and apply for licences for canons and such like to defend itself at sea. Having chartered it, the freighters then seek to cover their costs and make a profit by gathering exports to sell at the other end, and selling fares to passengers. This work wasn’t something done by passengers. They simply pay for their own passage, whether individually or collectively. The Jan 1637 Petition mentioned that the expected revenue from the return voyage would be at least £3000. This was nothing to do with the passengers, and was over and above any revenue from their fares.

+++

The Jan 1637 Petition didn’t use the word ‘charter’, but it referred to the “Freightors”. The primary dictionary definition of a freighter, one used from the late 16th C, is “A person who loads a ship, or who charters and loads a ship.”

The difference between Atwater’s construct of ‘chartering’ the

Hector and his one about the ‘company’ is that unlike the ‘company’ there was actually a chartering of the

Hector—in the sense just described, albeit not explicitly by the mention of the word itself. The company was imaginary, the chartering itself wasn’t imaginary, however it was

Atwater’s interpretation of the chartering—and Calder’s after him—that was, as you can see next.

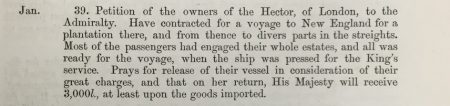

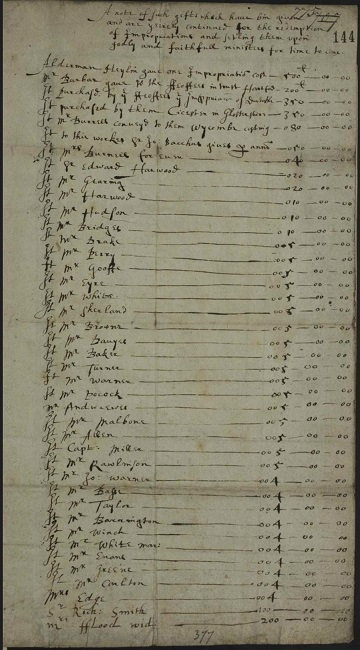

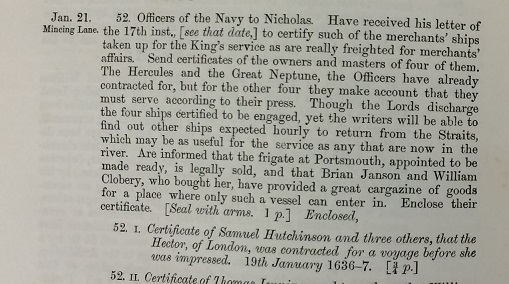

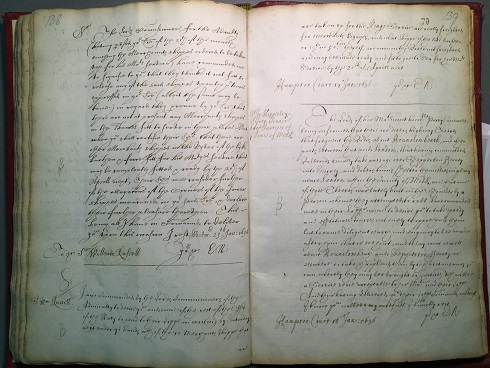

2.4. The Jan 1637 Petition

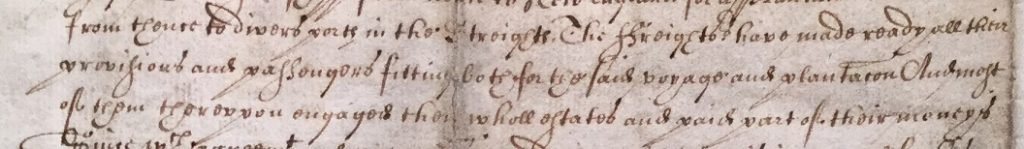

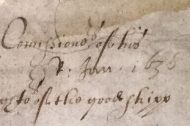

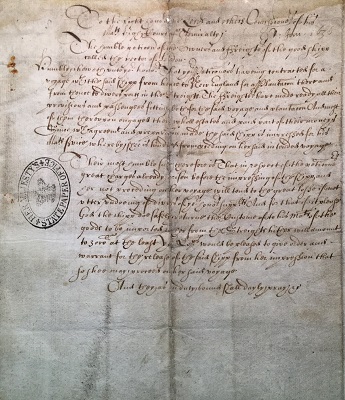

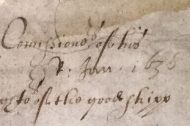

This Petition was a formal legal request to the Admiralty by the owners and freighters of the Hector to release it from impound. Petitions weren’t usually dated, and the “R: Jan . i636” between the right hand end of the title and the first line—‘R’ standing for ‘Received’ or ‘Recorded’—was inserted by a later hand, although there’s no need to doubt its accuracy:

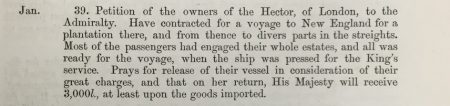

It seems that Atwater, or someone for him, searched in the Archives in London and among the colonial papers for America and West Indies 1636-38 found and transcribed this original document, footnoting it as “Petition of the Owners and Freighters of the Good Ship called the Hector of London. State Papers: Colonial.” View an image of the whole Petition here:

2.4.1. Overview

The owners and freighters of the Hector were petitioning the Admiralty. They—the owners and freighters—were parties to a contract for a cross-Atlantic sailing by the Hector, but it had subsequently been impounded by the Admiralty for its own services. This was their formal petition for its release. Their case was that much money had been invested in the enterprise, and some of the freighters in particular had invested their whole estates in the venture, which if the ship wasn’t released they stood to lose. They forecast that if the ship were allowed to proceed and returned safely, the import customs revenue of the goods she would bring back would come to at least £3000—a huge sum in those days.

What the freighters had done was to charter the ship from the owners. They had made a contract together. However, Atwater—and later Calder—implied that it was the passengers-to-be who had contracted, i.e. chartered, the ship and some had invested their whole estates in the venture. Atwater called them the ‘company of emigrants’ and Calder later called them the ‘group’, but they both evidently meant a network of future New Haven planters before they left England. This was the imaginary construct that Atwater created from the Jan 1637 Petition and that Calder later adopted. And it’s clear from the Petition that this was an incorrect interpretation:

Line 3 of the Petition said it was the “petition of the Owners and Freightors”.

Line 5 that “your Peticioners haveing contracted”.

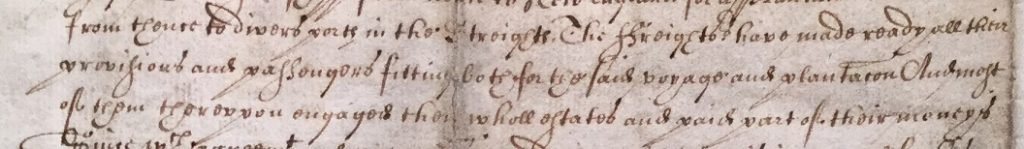

Lines 7-9 that “The Freightors have made ready … And most of them therevpon engaged their wholl estates”.

The Petition shows that the owners, freighters and passengers were distinct entities. But by fudging the distinction between the two usages of the word ‘company’, as seen above, Atwater could also fudge the distinction between owners and freighters and passengers, and claim that it was his ‘company’ that chartered the vessel, invested their capital and petitioned for its release. But the Petition is clear: The owners and freighters—not the passengers—were the petitioners; the owners and freighters had contracted, i.e. chartered the ship—not the passengers; and most of the freighters—again not the passengers—had engaged their whole estates. To engage lands was a legal term meaning to mortgage, i.e. most of the freighters had mortgaged their whole estates to raise the capital needed to send a trading vessel to the colonies. The ‘passengers’ who were emigrating from England for a new life abroad would hardly mortage their property prior to leaving the country—outright sell it, perhaps, but to mortgage would make no sense for an emigrant. Clearly, according to the Petition, the passengers had nothing to do with any of it. Let’s look more closely at the whole Petition, crucial as it is to both Atwater’s and Calder’s narratives.

2.4.2. Summary and transcription of the Petition

Before considering Atwater’s narrative surrounding the Petition, here’s a fuller summary of it, keeping faithfully to the plain and obvious meaning of the text:

+++

Lines 1-4: The owners and freighters of the Hector were petitioning the Admiralty

Lines 5-7: having made a contract for a voyage from London to New England for a plantation there and then on to other ports in the Straits.

Lines 7-8: The freighters had prepared all their provisions and passengers for the voyage and the plantation.

Lines 8-9: Most of the freighters had pledged their entire capital doing this and had already paid some instalments.

Lines 10-11: Subsequent to this contract and the preparations the ship had been impressed for the King’s service and was now prevented from sailing.

Lines 12-15: Therefore the petitioners’ suit was that since some of them stood to lose a lot of money because of this, if not be utterly ruined,

Lines 15-18: and since if the ship were allowed to proceed and returned safely, the import customs revenue of the goods she would bring back would come to at least £3000,

Lines 18-21: they requested a warrant for the release of the ship from the King’s service.

Notes:+Read more

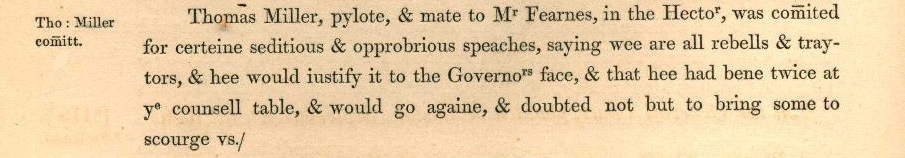

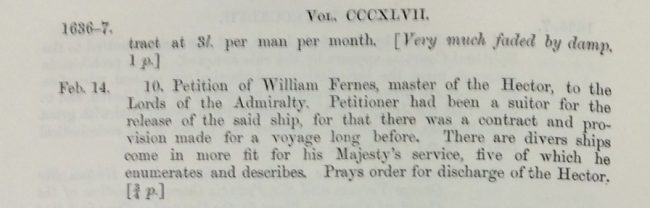

Lines 1-4. The contemporary meaning of a ‘freighter’, as mentioned above, is “A person who loads a ship, or who charters and loads a ship.” The master or captain of the ship, William Fernes, in a follow-up petition of 14 Feb 1636/7 said he had been a previous suitor for the release of the Hector, referring presumably to the Jan 1636/7 Petition, and therefore probably a freighter or perhaps an owner. The owners would have been hands-off investors, probably the same owners who 6 months earlier on 23 Jan 1635/6 had submitted an application to arm the Hector: Henry Croane, James Sherley, and William Hunte of London Mechants and Richard Fearmes of Whapping Mariner, with others.

+++

Lines 5-7. The ‘contract’ here is the nearest the Petition got to the term ‘chartering’ used so often by Atwater. Of course the contract was clearly between the owners and the freighters, as mentioned above, and not with the passengers. There was chartering but it was between the owners and the freighters, not by or with the passengers. The passengers, like the provisions, were part of the preparations the freighters had made.

+++

The Calendar entry misread “ports” here as “parts”, and Atwater did too. “Ports” indicated the commercial aspect of the voyage more clearly. Here is the Calendar entry:

+++

+++

Lines 7-8. The passengers for the voyage were introduced here. The passengers were not the petitioners. Nor were the passengers either the owners or the freighters. The freighters had made the preparations; they had enlisted passengers and gathered sufficient provisions for the voyage and for the plantation.

+++

Lines 8-9. Most of the freighters had pledged (engaged) their entire capital (whole estates) doing this (thereupon) and had already paid some instalments (moneys). The Calendar entry misinterpreted this: that most of the passengers—rather than the freighters—had engaged their whole estates. This was clearly an error. The text of the Petition says: “The Freightors have made ready all their provisions and passengers fitting both for the said voyage and plantacion And most of them therevpon engaged their wholl estates…”. The plain and obvious meaning of “most of them” is “most of the freighters”. Those who had prepared all the provisions and passengers were the ones who had engaged their whole estates. Atwater also misinterpreted the Petition in this way, and Calder followed him.

+++

Lines 12-18. The petitioners were the owners and freighters, not the passengers. The passengers were neither petitioning nor claiming utter ruin. The petitioners probably exaggerated their potential losses to bolster the Petition. Suffering ‘utter ruin’ was a frequent claim in complaints of the time, and the £3000 potential return may have been ambitious too.

And for a transcription of the whole document

+Read more

1. To the Right Honorable ike Lords and others Commissionors of his

2. Majestys High Court of Admiralty. [R: Jan . i636]

3. The humble petition of the Owners and Freightors of the good shipp

4. called the Hector of London.

5. Humbly sheweth vnto your honors That your Peticioners haveing contracted for

6. a voyage with the said shipp from hence to New England for a Plantacion there and

7. from thence to divers ports in the Streights. The Freightors have made ready all their

8. provisions and passengers fitting both for the said voyage and plantacion And most

9. of them therevpon engaged their wholl estates and paid part of their moneys

10. Since which agreement and preparacion made the said shipp is impressed for his

11. Majestys service whereby shee is hindered from proceding on her said intended voyage

12. Their most humble sute therefore is That in respect of the petitioners

13. great charges already arisen before the impressing of the shipp, and her

14. not proceding on her voyage will tend to the great losse if not

15. vtter vndoeing of divers of your honors suppliants And for that if it please

16. God the shipp doe safely returne the Custom of to his Majesty of the

17. goods to be imported in her from the Streights hither will amount

18. to 3000£ at the least Your Lordships would be pleased to give order and

19. warrant for the release of the said shipp from her impression that

20. so shee may proceed on her said voyage

21. And they as in duty bound shall dayly pray &c

As mentioned above, this Jan 1637 Petition, along with his 2 constructs of the ‘company’ and its ‘chartering’ of the vessel, formed the 3 fundamental elements of Atwater’s narrative of the emigration. Indeed the Petition was probably the main source of the 2 constructs, despite it not actually using either word. Be that as it may, it was central to his argument and needs to be looked at in detail.

2.4.3. Atwater’s narrative surrounding the Petition

Aside from Davenport’s and Eaton’s family circles, and his 7 citizens of London, plus an eighth called John Evance, Atwater didn’t—unlike Calder—suggest any other names of passengers. However, he developed a complex narrative surrounding this Jan 1637 Petition in which he argued that passengers were deliberately unnamed.

Regarding these unnamed passengers lines 7-9 of the Petition are the important ones:

Here’s a transcription of lines 7-9 of the document and a summary of Atwater’s 5 interpretations of them:+Read more

1. Literal transcription: The Freightors have made ready all their provisions and passengers fitting both for the said voyage and plantacion And most of them therevpon engaged their wholl estates and paid part of their moneys …

+++

2. Atwater’s transcription: the freighters have made ready all their provisions and passengers, fitting both for the said voyage and plantation, and most of them thereupon engaged their whole estates and paid part of their moneys. …

+++

Comment: Ignoring the word ‘ports’ mentioned above, Atwater’s transcription of the original Petition was accurate apart from the addition of punctuation, and details of spelling. The spelling was irrelevant, but the punctuation could have implications, as here perhaps.

+++

3. Atwater’s 5 interpretations:

Category 1 (p 36):

+++

1. “The organization of a company of emigrants was so far forwarded in January of the following year that they had chartered a vessel, “made ready all their provisions and passengers, fitting both for the said voyage and plantation, and most of them thereupon engaged their whole estates.””

2. “While these preparations were in progress, Davenport doubtless kept himself out of sight as much as he conveniently could, both on his own account, and for the sake of the expedition. … If it had been known that those who had chartered “the good ship Hector,” to carry them to New England, and had engaged their whole estates in preparing for the voyage, were to have the former vicar of St. Stephen’s as their leader, their undertaking might have been extinguished with as little regard to the rights of property as that of the feoffees had been.”

+++

Category 2 (pp 50-2):

+++

3. “The reader will have noticed that the names of the freighters are withheld in all these negotiations for the release of their ship. It is alleged that many will suffer, and perhaps be undone, but there is nothing to call attention to any individuals as engaged in the enterprise.

4. “The association of adventurers which chartered the Hector would naturally adopt similar methods and similar rates.”

5. “Before the Hector sailed, the company which chartered her had so increased that it became necessary to hire another vessel to accompany her on the voyage …”

Since this Petition was crucial to Atwater’s narrative of events—and to Calder’s after him

—it is necessary to analyse his 5 interpretations more closely. For details

+Read more

Atwater used the Petition in 2 separate contexts—the first actually in the chapter preceding the chapter devoted to the Hector—and his 5 interpretations fall into 2 different categories, corresponding to the 2 contexts, as quoted above. Category 1 comprises interpretation nos.1-2 on p 36 and Category 2 comprises nos.3-5 on pp 50-52. The 2 different contexts relate to the 2 different usages of Atwater’s construct of the ‘company’, thus the 2 different categories of interpretations do likewise.

+++

Category 1 (interpretation nos.1-2) portrayed the emigrants—Davenport’s ‘company’ from St. Stephen’s Coleman Street, i.e. the passengers—as the ones who had chartered the vessel and engaged their whole estates in the venture. As shown above in the notes to lines 7-8 of the Petition, this was incorrect. It was the freighters who had done so. Conversely, his second Category of interpretations, nos.3-5, was truer to the document and portrayed the freighters or association of adventurers—or the ‘company’ in that legal or commercial sense—as the ones who had chartered the vessel and engaged their whole estates in the venture.

+++

Atwater’s argument that the passengers were deliberately unnamed in the Petition obviously relates to Category 1. He implied that Davenport had deliberately withheld his own name from the Petition in order not to call attention to himself, and his followers did likewise. Atwater certainly cited evidence for Davenport keeping a low profile generally, but to extend it to the Petition specifically is a speculative argument from silence, and in any event depends on the erroneous interpretation of who had chartered the vessel.

+++

Without going further into unnecessary detail about the slight differences between the individual interpretations within the categories, their common denominators are clearly different: Category 1 portrayed Davenport’s followers as the ones who had chartered the vessel, Category 2 portrayed the freighters or ‘company’ in its larger legal sense of an association that included adventurers as doing so. Whether this fudging of the distinction between the entities involved was deliberate or whether it was the result of his constructs not neatly fitting the documentary evidence doesn’t matter, but the net result was that Atwater’s narrative misinterpreted the Jan 1637 Petition, and his convoluted account of the composition of his ‘company’ is unclear and imaginary. His successor Calder sidestepped the complexities and mentioned neither freighters nor even passengers in her brief narrative. She mentioned owners once as the 1637 petitioners, but for her it was simply her ‘group’ of relatives of Eaton and followers of Davenport that “chartered the Hector of London” without providing any evidence to support the assertion, see below.

In sum, enough should have been discussed in this section to show that Atwater was apparently the first to develop the notion that a sizeable number—or ‘company’—of future New Haven planters emigrated in the Hector in 1637, although he acknowledged that no passenger list as such had been found.

2.5. 1905: EJ Brockett

Atwater was writing at the turn of the 19th and 20th C when the drive to trace the origins of New England’s early settlers intensified, and other descendants of the founders of New Haven than Atwater were compiling their genealogies and wanting to find a passenger list of their ancestors’ arrival. For example, in the Historical Introduction to his book of 1905 EJ Brockett described the formation of the new plantation and how his ancestor John Brockett was a member of it. Then in a final extended note to it EJB collected and slightly paraphrased some of Atwater’s observations on the Hector, and although EJB didn’t state outright that John Brockett arrived on the Hector, the implication was that he did.

Then a generation later the implications became stronger.

3. 1934: Calder’s The New Haven Colony

When Isabel MacBeath Calder published The New Haven Colony in 1934 the seed of an actual passenger list of the Hector‘s 1637 voyage was sown. As we shall see, Calder didn’t herself reproduce a ‘passenger list’ in the sense of a formal document drawn up by the officer of a ship or of a port of departure or arrival, as later writers implied; she only listed the members of the ‘group’ that she claimed emigrated. If she had located an actual passenger list during her researches in London archives, she surely would have reproduced and referenced it, but she evidently didn’t find one. Instead she collated a number of other disparate documents in support of her own composition of the ‘group’, and we analyze these below. Nonetheless, it was this detailed composition of hers of the ‘group’ that has become a passenger list. And now in all later accounts, references to, and quotations from, a Hector passenger list have their origin in the opening chapter of Calder’s book. Some may be to, from or via a later source like Lancour, Boyer, or Filby, but Calder is their ultimate source.

You might say this is splitting hairs, and ask: “What is the difference between on the one hand a detailed mention of all the names in a group of emigrants that chartered the Hector in London and arrived in Boston, and on the other hand a passenger list? Actual passenger lists themselves can get destroyed.” Aside from the essential difference between primary and secondary evidence, there might not be an unbridgeable difference if—and it’s a big if—there is valid contemporary evidence of the composition of the ‘group’ in London, of its chartering the ship there and of them all arriving in Boston. This is the crux of the matter: Valid evidence of all three of them would be equivalent to a passenger list. Unfortunately, careful research shows that there is valid evidence for none of these three. This webpage analyzes why.

As the title indicates, Calder’s book concerns the New Haven Colony. Eleven of its twelve chapters are situated in New England, with just Chapter 1 in old England. This first chapter narrates a pre-history of the planters in old England as an introduction to the subsequent history of their plantation in New England. In particular, Chapter 1 sets a Puritan context for the developing events in the rest of the book. It is entitled “St. Stephen’s, Coleman Street”, the name of a parish in the City of London where Rev John Davenport was some time vicar. Within Chapter 1, Calder’s portrayal of the contemporary political and religious environment in old England leads up to a dramatic climax in its final two paragraphs on pp 29-31 portraying a ‘group’ of politically and religiously like-minded people forming around Rev John Davenport and escaping a hostile situation in England by emigrating to begin a new life across the seas.

3.1. The ‘group’

Where Atwater’s discussions of the nature of his ‘company’ were extensive and complex, Calder’s of her ‘group’ were brief and simplistic. Where Atwater’s names of the members of his ‘company’ were tentative and few, Calder’s of her ‘group’ were confident and many. Where Atwater was fairly transparent in his use of sources, Calder seemed at times deliberately obscure.

Atwater devoted a whole chapter and more to the Hector, Calder just 2 paragraphs. It’s as though Calder took Atwater’s narrative as fact, but without acknowledgement. Atwater named about a dozen members of his ‘company’, Calder named about 48 of her ‘group’. Atwater struggled to harmonize various sources, Calder footnoted incompletely and inaccurately.

But the similarities between the two narratives were greater than their differences. We saw how Atwater constructed his narrative upon 3 main foundations: the ‘company’, the ‘chartering’ and the Jan 1637 Petition, and how the first two were misinterpretation of the third. Calder did the same. She may only have mentioned the second two in passing—whether assumed as fact or obscured as awkward evidence—but they were foundations sure enough.

The essence of Calder’s narrative of the ‘group’ as told in the final 2 paragraphs of her Chapter 1 is as follows:

[Penultimate paragraph]

1. Davenport and Eaton organized a company to begin a plantation in the New World.

2. The nucleus of the group was composed of … [16 names]

3. With this nucleus many … coalesced [13 names] …

4. Among others who … cast in their lots with the emigrants, were [19 names] …

[Final paragraph]

5. The group chartered the Hector …

6. On June 26, 1637, John Winthrop recorded the arrival of the group …

The penultimate paragraph focused mainly on names, the final paragraph on dates.

Let’s look at her narrative in more detail in what follows.

3.2. Calder’s Chapter 1 pp 29-31

What Calder actually said on pp 29-31 and the evidence she claimed supported it (her footnotes) can now be assessed. In particular there are 6 sentences that shape the climax of her narrative and are crucial to the composition of the ‘group’—and therefore subsequently of the passenger list. Since her book isn’t currently available on the internet, you can find this climax of her Chapter 1—these pp 29-31—with 6 sentences highlighted in bold in their wider context here: +Read more

During Davenport’s stay in the United Netherlands, he had received glowing accounts of New England from John Cotton.81 Unable to foresee the changes which the ensuing decade was to usher in in England, Davenport and Eaton organized a company to begin a plantation in the New World. The nucleus of the group was composed of the leaders and their families: John and Elizabeth Davenport, who left their infant son in the care of the noble lady to whom the Long Parliament later entrusted the children of Charles I; Theophilus Eaton, who carried with him all the books of the Massachusetts Bay Company,82 and the authorization of the grantees of the Earl of Warwick to negotiate with the settlers on the Connecticut River regarding title to their lands;83 Anne Eaton, daughter of George Lloyd, Bishop of Chester, and widow of Thomas Yale,84 the second wife of Theophilus Eaton; Mrs Eaton, his mother; Samuel and Nathaniel Eaton, his brothers; Mary Eaton, the daughter of his first wife; Samuel, Theophilus, and Hannah, the children of his second wife; Anne, David, and Thomas Yale, the children of Anne Eaton by her former marriage; Edward Hopkins, who September 5, 1631, had married Anne Yale at St. Antholin’s in London;85 and Richard Malbon, a kinsman of Theophilus Eaton, and perhaps one of the subscribers to the company of feoffees for the purchase of impropriations and a member of the Massachusetts Bay Company.86 With this nucleus many inhabitants of the parish of St. Stephen, Coleman Street, coalesced: Nathaniel Rowe, sent overhastily and without due consideration by his father, Owen Rowe, who intended to follow;87 William Andrews, Henry Browning, James Clark, Jasper Crane, Jeremy Dixon, Nicholas Elsey, Francis Hall, Robert Hill, William Ives, George Smith, George Ward, and Lawrence Ward, all with family names found in the accounts of the churchwardens of the parish. Among others who desired to begin life anew in the wilderness across the seas, and who cast in their lots with the emigrants, were Ezekiel Cheever of the parish of St. Antholin, Edward Bannister, perhaps of the parish of Saint Lawrence, Old Jewry, and Richard Beach, Richard Beckley, John Brockett, John Bud, John Cooper, Arthur Halbidge, Matthew Hitchcock, Andrew Hull, Andrew Messenger, Mathew Moulthrop, Francis Newman, Robert Newman, Richard Osborn, Edward Patteson, John Reader, William Thorp, and Samuel Whitehead, probably all from the neighborhood.

+++++

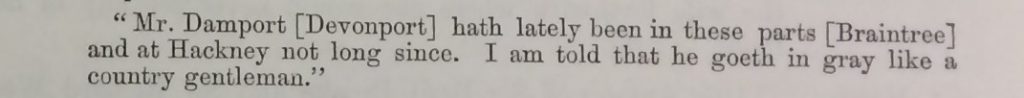

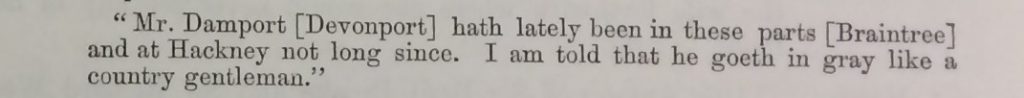

The group chartered the Hector of London, an almost new vessel of about two hundred and fifty tons burden,88 which had already made one voyage to Massachusetts Bay.89 After they had engaged their whole estates in the venture, paid their passage money, and provisioned the vessel, the Hector was impressed for the service of the crown. Although the owners petitioned for its release, January 19, 1637,90 a delay of several months ensued. During this period of enforced waiting, Archbishop Laud learned of Devonport’s presence at Braintree and Hackney,91 but there is no evidence that he made any effort to apprehend him. Early in May the Hector was freed.92 On June 26, 1637, John Winthrop recorded the arrival of the group from London at Boston in New England.93

It is this climax and final two paragraphs of Calder’s Chapter 1 and her construct of the ‘group’ that are analysed in more detail below by means of these 6 sentences as her proof statement. But first, to give more context to pp 29-31 here are some observations on Chapter 1 as a whole +Read more

Although clearly also dependent on Atwater at several points in her Chapter 1 prior to the concluding 2 paragraphs, Calder didn’t acknowledge him in her footnotes. Somewhat hypocritically, she criticized him of failing to exhaust manuscript sources in England, and described his History as “far from adequate”. Calder’s narrative in Chapter 1 nonetheless echoed Atwater’s in 2 substantial ways:

+++

1. The pre-history in London. In Chapter 1 Calder echoed and summarized more briefly much of Atwater’s fuller narrative, but developed it specifically with a view to naming the emigrants. Following Atwater, Calder painted a picture of the parish of St Stephen’s Coleman Street in the City of London and the early career of John Davenport as its Vicar, who gradually became more sympathetic to the Puritan cause and fell foul of the higher ecclesiastical authorities, and fled to the Netherlands, returning later to become the spiritual leader of a project to establish a colony in New England. Calder’s narrative led to the emergence of her ‘group’, as did Atwater’s to the emergence of his ‘company’.

+++

2. Its imagined structural frame. The same 3 structural elements that framed Atwater’s narrative of the emigration also underpinned Calder’s. These were the constructs of the ‘company’ and the ‘chartering’ of the vessel, and the Jan 1637 Petition—on which the other two were erroneously based. As we have seen above, Calder focused far more on the first element which she termed the ‘group’, but all three were fundamental to her narrative. As with Atwater, these three motifs were woven so thoroughly into the fabric of the narrative that it’s difficult to unravel them from the overall pattern. The same applies to Calder, but if we are to understand the emergence of a ‘passenger list’ they have to be. Her treatment here was much briefer than Atwater’s. Where he devoted a whole chapter and more to the Hector, Calder had one paragraph. She therefore took for granted much of what Atwater had attempted to evidence, like the ‘chartering’ and the Jan 1637 Petition. It’s as though Calder took Atwater’s narrative as read, needing no further discussion.

+++

Calder’s brief treatment allows us to see its imaginative structural frame clearly and how she inserted documented facts into a framework of imagined constructs. Her final paragraph contains a number of documented facts, but they are framed by the imagined constructs of her ‘group’ and its ‘chartering’ of the ship. The documented facts are important but peripheral to the main point of the paragraph, whereas the imagined constructs are pivotal to it. The paragraph goes:

1. “The group chartered the Hector of London”

2. [some documented facts]

3. “On June 26, 1637, John Winthrop recorded the arrival of the group from London at Boston in New England.”

As a pattern, this is:

1. Imagined introductory construct—pivotal

2. Documented facts—peripheral

3. Imagined concluding construct—pivotal

Whether deliberate or not, this is misleading. It creates an impression that the constructs are evidenced by documents like the intervening facts are.

3.2.1. Calder’s argument: the 6 sentences

In this and the next section you can find an analysis of Calder’s argument and evidence for her detailed composition of the ‘group’ of emigrants, in other words her proof statement for its formation and emigration. You will find the argument encapsulated in 6 sentences in the climax of chapter 1, quoted above, and her evidence in their associated footnotes. These are all quoted and analyzed—the sentences in this section, the footnotes in the next.

Sentences 3-4 provided the bulk of the names you will find on an internet Hector passenger list. They introduced two lists of 32 (13+19) names of emigrants who weren’t part of Eaton and Davenport’s family circles. Calder herself didn’t refer to these lists as a passenger list as such, but an abstract of all 6 sentences shows the progression of her ideas and leaves no doubt that she was supplying a list of passengers.

Sentences 1 & 2: “Unable to foresee the changes which the ensuing decade was to usher in in England, Davenport and Eaton organized a company to begin a plantation in the New World. The nucleus of the group was composed of the leaders and their families”.

For a commentary Read more

This was where Calder introduced her construct of the ‘group’. In sentence 1 it was “a company”—as it had been with Atwater—and now in sentence 2 it became “the group”. Looking back later from New Haven and the Fundamental Agreement of 1639 it is obviously true that Davenport and Eaton brought together a community of immigrants to begin a plantation in the New World. But whether what they did some years previously in London was as deliberate, immediate and systematic as Calder’s phrase that they “organized a company” at that time implied, required more evidence than she supplied, like correspondence, records of meetings or anything to demonstrate the systematic creation of a body of planters. But all Calder provided here was a list of 16 close relatives of Davenport and Eaton. A party of relatives like this would seem a natural collection of people thinking to emigrate, but coupled with the notion of organizing a company, Calder’s description of this family circle as “the nucleus of the group” created an impression of it as the active heart of a larger body, or the driving force within the organization. Again, it may well have become so later in New England—especially in the sense of a ruling clique—but more evidence of it in London was required to support her claim. Atwater had previously also used the concept of a nucleus within the ‘company’, although its composition was different to Calder’s.

+++++

But Calder’s list of the 16 relatives with its footnotes, was just that: a list of relatives; it was neither evidence for them being the active heart of a larger body, nor was it part of a passenger list.

Sentences 3 & 4: “With this nucleus many inhabitants of the parish of St. Stephen, Coleman Street, coalesced: [13 names] all with family names found in the accounts of the churchwardens of the parish. Among others who desired to begin life anew in the wilderness across the seas, and who cast in their lots with the emigrants, were [19 names] probably all from the neighborhood.”

For a commentary Read more

Where did Calder get these 32 names from?

+++++

1. Calder provided just 1 single

reference for all these 32 names, and it was with respect to just the first name in her list of inhabitants of the parish of St Stephen, Coleman Street:

Nathaniel Rowe.

Atwater had previously included the same reference in a discussion of some length about Nathaniel, and based on weak evidence had suggested that he came across in the

Hector. Calder’s simple reference provided no evidence that he was an inhabitant of the parish of St Stephen, Coleman Street.

Calder thus named all these 32 men as part of a group of emigrants without any reliable evidence.

+++++

2. Her claim that they were inhabitants of the parish of St Stephen was that they all had “family names found in the accounts of the churchwardens of the parish.”

But this is no evidence. The family names were Rowe, Andrews, Browning, Clark, Crane, Dixon, Elsey, Hall, Hill, Ives, Smith, Ward, all of which are relatively common English surnames. Even the occurrence of a less common one like Elsey in the churchwardens’ accounts is no proof that a Nicholas Elsey was there. Unless the first names were also recorded in such a way that shows that they were the men in question,

a connection between them and New Haven immigrants is purely speculative. No doubt had a Nicholas Elsey been recorded in the churchwardens’ accounts, Calder would have mentioned it. Atwater sensibly said, “Other New Haven names than those of Evance and Eaton are found on the parish register of St. Stephen’s; but the names are such as might be found elsewhere in England.”

+++++

3. The same applies to Calder’s second list of 19 men. First in the list was “Ezekiel Cheever of the parish of St. Antholin”, then “Edward Bannister, perhaps of the parish of Saint Lawrence, Old Jewry”, then the remaining 17 names “probably all from the neighborhood”.

Calder supplied no evidence for Ezekiel Cheever.

Atwater had similarly suggested that Ezekiel Cheever was a member of the ‘company’ and had supplied no evidence.

There is a record of the baptism of an Edward Banister in St Lawrence Old Jewry on 4 Feb 1609, one of 13 children of Francis Banister, Citizen and Joiner, and his wife Elizabeth.

And an “An, daughter of francis Banister a servant of Mr Thomas Collwell” was baptized 27 Jul 1620 in St Stephens Coleman St.

This Francis may have been Edward’s elder brother, and baptized 28 May 1598, but whether Edward survived or later joined a group from Coleman St or emigrated would be speculation.

+++++

4. The remaining 17 of Calder’s second list she said were “probably all from the neighborhood”. Apart from supplying no authority to back up her suggestion, did her use of ‘neighborhood’ signify anything meaningful in the early 17th C City of London? Its area was approximately 1 square mile,

and could probably be crossed from side to side within a half hour. Sure, St. Antholins was less than half a mile from Coleman St, as was St Lawrence Old Jewry, but none of the City’s 110 parish churches were much further.

+++++

5. Atwater had suggested a few names of members of the ‘company’ but was sensibly more

sceptical. But why Calder didn’t include some of his names in her lists is unclear.

+++++

6.

All Calder’s 32 names are in the columns of names on the top part of the Fundamental Agreement, rather than those who signed lower down. Click

here for an image of the page. In addition to following Atwater—selectively and without acknowledgement—

this could have been the main source for her list of names. But if so, it is no evidence that they came on the

Hector in 1637. They could equally have come on another vessel on another trip, or have come to New Haven from elsewhere in New England.

Sentence 5: “The group chartered the Hector of London”.

For a commentary Read more

This sentence, or part of a sentence, has been highlighted as one—perhaps the crucial one—of the 6 main points in Calder’s imaginary narrative of the ‘group’ that emigrated. But the progression of the narrative in the whole paragraph it introduced shouldn’t be overlooked, particularly in the way it placed documented, but peripheral, facts in a framework of imagined, but pivotal, constructs. We highlighted the pattern above, but it is worth repeating:

1. Imagined introductory construct—pivotal

2. Documented facts—peripheral

3. Imagined concluding construct—pivotal

+++

As for this sentence 5 itself, we saw that Atwater similarly claimed that “a company of emigrants was so far forwarded in January of the following year that they had chartered a vessel”. Atwater had supported this—mistakenly—by reference to the Jan 1637 Petition. Calder didn’t support her statement here with any reference, but simply stated it as [assumed] fact, and her footnotes 88 and 89 in the rest of the sentence referred to documented facts to do with the ship rather than the alleged chartering of it. She referenced the Jan 1637 Petition in footnote 90 a couple of sentences later with the statement that “the owners petitioned for its release, January 19, 1637”, which is again documented fact, albeit only partially correct. Embedding documented facts in a framework of assumed or imaginary fact like this is misleading, whether deliberate or not. This Sentence 5 introduced the pattern shown above:

1. “The group chartered the Hector of London”

2. [some documented facts]

3. “On June 26, 1637, John Winthrop recorded the arrival of the group from London at Boston in New England.”

+++

This was the only place in her narrative where Calder mentioned the ‘chartering’ construct. She simply stated it without explanation. It was nonetheless pivotal to her narrative, and one its 3 main foundations. But it was a false foundation. Calder gave no evidence to support the claim. Indeed there was none. It was a leap of imagination and contradicted the Petition of Jan 1637, which says that it was the freighters who had contracted, i.e. chartered, the ship. Atwater had made the same false claim, and Calder reproduced it.

+++

Calder’s ‘group’ in this Sentence 5 was the other main construct in Calder’s narrative. As discussed further under Footnote 90 Comment 2 item 1. 90a below, Calder should at least have referred to the Jan 1637 Petition here after this claim that “The group chartered the Hector of London”, and indeed to Atwater. Instead, however, she only referred to it later with respect to the less important detail of its date, and didn’t refer to Atwater at all. Calder’s ‘group’ was of course the 48 or so names she had just listed in the preceding paragraph, whereas the Jan 1637 Petition was clear that it was the owners and freighters who chartered the vessel. If that was why she didn’t cite it here, it was dishonest.

Sentence 6: “On June 26, 1637, John Winthrop recorded the arrival of the group from London at Boston in New England.”

For a commentary Read more

This is the final sentence of the chapter, its punchline, the completion of the climax. The group of emigrants had arrived. Calder had told their story in England and the next chapter proceeded to Massachusetts Bay. The 5 individuals that Winthrop recorded arriving had here in Calder’s imaginative narrative grown into the ‘group’ of 48. Lancour then suggested that Calder had supplied a passenger list and others followed his lead. But it was a misleading lead. Winthrop recorded the arrival of no such group—just of 5 individuals, one of whom was unnamed, and another of whom was an English Lord who didn’t join the Colony.

3.2.2. Calder’s evidence: her footnotes 81-93

At first sight the scholarly appearance of Calder’s 13 footnotes in little more than 2 pages of text inspires confidence. But on closer inspection, they are specious, every one of them. The main function of footnotes is to supply reliable evidence in support of an argument or discussion. Calder was arguing here for two propositions: the detailed composition of her ‘group’ of emigrants and their sailing from London to Boston, but not one of the 13 footnotes supplies reliable evidence. Nor can a single one of them be cited further as reliable evidence of a passenger list. Even the last one, the punchline no.93, is misleading: it certainly is a reference to Davenport, Eaton and Hopkins arriving in Boston on the Hector in 1637, but not, as Calder uses the reference, to the arrival of the large ‘group’ of 48 or so that she had constructed.

To justify this damning criticism, a comment follows each of the 13 footnotes quoted in this section, providing images where the source isn’t readily accessible. The focus here is on their relevance to the climax of the chapter, i.e. the formation and emigration of the ‘group’—and subsequently to the alleged passenger list. Since 6 sentences were highlighted above as encapsulating Calder’s overall argument, her evidence to validate it—these footnotes 81-93—don’t necessarily attach directly to one of these 6 sentences; they were her evidence to validate the overall argument.

Some are references to Massachusetts publications, mostly accessible online or to local readers in the States, others are to UK State Papers Domestic, not so generally accessible, and then there are several manuscript references, inaccessible to the general reader. In the ‘Bibliographical Note’ at the end of her book Calder provided details of where in England the records were located, but it took this researcher, familiar with UK archives, a long time to track them all down.

If you don’t have time to read the following analysis of all the footnotes, that of no.86 and no.90 are representative of their overall quality.

Calder’s book as a whole received largely unfavorable reviews, like those from contemporary colleagues at Harvard and Stanford. One said, “Her footnotes are repeatedly incorrect“.

Footnote 81: John Davenport, A Sermon Preach’d at The Election of the Governor At Boston in New-England. May 19th 1669 (1670), p.15, reprinted in Colonial Society of Massachusetts Publications, X, 6.

Comment:+Read more

The sentence this footnote attached to was introductory to the paragraph. It referred to a sermon Davenport delivered many years later and had no relevance to passengers’ names. Nor did the sermon suggest that he set about organizing his own company, as Calder’s following sentence said (sentence 1 above). Nor did the sermon suggest that the company’s nucleus was composed of the leaders and their families (sentence 2). If anything, the sermon suggested that Cotton was inviting Davenport to come on his own, and to the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Footnotes 82-86:+Read more

These 5 footnotes purport to supply evidence for a ‘nucleus of the group’, which in Calder’s view comprized Mr and Mrs Davenport and Theophilus Eaton’s family party. Her sentence 2 highlighted above claimed, “The nucleus of the group was composed of the leaders and their families” and the next few sentences itemized members of Davenport and Eaton’s family circle. But all that these footnotes 82-86 actually supplied evidence for was the existence of these people, not that they were the nucleus of any group that sailed on the Hector in 1637. Without such evidence the list of these relatives was just that, a list of relatives that Calder had found some references to. Only because these footnoted references to the relatives are a part of Calder’s arguments in pp 29-31, which were later to be cited as the source of the passenger list, and because as a result these names appear on the ‘list’ on the internet, is it necessary to evaluate them here.

+++

Atwater had also mentioned some of these names as the nucleus of the company, but not entirely the same ones and also added several citizens of London. Of Calder’s list Atwater didn’t mention Mrs Eaton, his mother; Mary Eaton, the daughter of his first wife; or Samuel, Theophilus, and Hannah, the children of his second wife; but did suggest that John Evance and his wife Anne Young were among them. Why Calder’s list varied is unclear.

Footnote 82: Frances Rose-Troup, The Massachusetts Bay Company and Its Predecessors, p.104.

Comment:+Read more

This is available online. The reference simply mentioned Theophilus Eaton taking all the books of the Massachusetts Bay Company with him to New England, date unspecified. As with Edward Hopkins, re footnote 85 below, we know from Winthrop that Eaton sailed into Boston in 1637 on the Hector, but the item referred to in this footnote neither mentioned that, nor supplied evidence of the existence of a ‘nucleus of the group’ that emigrated to New Haven. Nor was it directly relevant to the passengers’ names.

Footnote 83: Egerton MSS, 2648, fol.1.

Comment:+Read more

As with footnote 82 this British Library manuscript’s authorization will have no relevance to our enquiry into Calder’s evidence for the composition of a group that emigrated to New Haven, into which the Connecticut River doesn’t flow. It appears to refer to the controversial Warwick Patent.

Footnote 84: William Fergusson Irvine, ed., Marriage Licenses Granted within the Archdeaconry of Chester in the Diocese of Chester, I, 117.

Comment:+Read more

Vital records, such as this marriage license of a member of Theophilus Eaton’s extended family, will not provide evidence that the person was part of a group that emigrated on the Hector to New Haven. If by some extraordinary circumstance this one did, Calder would without question have quoted in full.

Footnote 85: Harleian Society Publications, VIII, 65.

Comment:+Read more

As with footnote 84 a vital record like this of Edward Hopkins’ marriage in 1631 will not provide evidence that he or his bride were part of a group that emigrated to New Haven on the Hector. However, Hopkins did indeed sail on the Hector in 1637, as Winthrop recorded, but he was neither on the subsequent list of Freemen of New Haven nor its Fundamental Agreement.

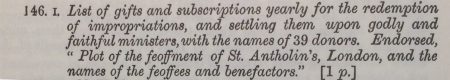

Footnote 86: Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, 4th Series, VI, 344-345; State Papers, Domestic, Charles I, DXV, no.146i.

Comment:+Read more

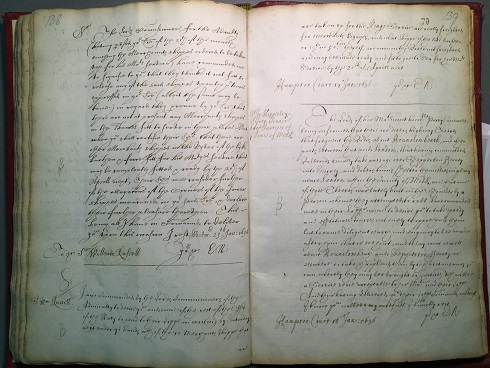

The two items referenced in this footnote are further illustrations of Calder’s evidence having little or no connection to the matter at issue: the composition of Calder’s ‘group’, or in this case its nucleus. The first item is a letter from Theophilus Eaton to Winthrop and the second a somewhat enigmatic six-sided document in the English State Papers, Domestic, endorsed on one side as “The plot of the feofment of S. Antholins” which we will refer to for short as ‘the Plot’.

+++

It is only worth taking time analyzing these two items in order to demonstrate their lack of relevance. Calder cited them concerning Richard Malbon, whom she named as part of the ‘nucleus of the group’, being a relative of Theophilus Eaton. But in fact the letter and ‘the plot’ each only contain one isolated reference to someone surnamed Malbon or Malbone, and neither provides any evidence that he was a member of a group that arrived in Boston on the Hector in 1637, nor part of its nucleus.

+++

Richard Malbon. A Mr Richard Malbon was certainly a signatory to the Fundamental Agreement, so was in New Haven by 1639, and was on the list of Freemen. He was also one of the 12 leading members, and the early records mention him often as a prominent figure. Evidence can thus well support him being described as a member of the nucleus of the early community in New Haven. By contrast, Calder claimed that he was so in England beforehand as well, and gave no evidence to support the claim. Likewise Atwater, who named him in a list of members of the nucleus of the ‘company’ in England, without any evidence:

“Besides these who were related to Davenport, as his former parishioners, or to Theophilus Eaton by family ties, several citizens of London joined the company. Not all of them can now be distinguished from those who came from other parts of the kingdom, but there is more or less authority for including in such a list the names of Stephen Goodyear, Richard Malbon, Thomas Gregson, William Peck, Robert Newman, Francis Newman, and Ezekiel Cheever.

+++

The London men with their families forming the nucleus of the company, other families or companies from the rural counties became united with it.”

If Richard Malbon was a cousin of Eaton he may well have been in close contact with Eaton in England beforehand and an active supporter of his plans. On the other hand, he may not have. He may just as well have arrived in New England separately and joined Eaton thereafter. The evidence Calder supplied neither supports the former nor disproves the latter. In what follows, Calder’s lack of evidence, both for Richard Malbon being a member of the nucleus of her ‘group’ in England and by extension, a passenger on the Hector in 1637 is analyzed.

+++

1. Eaton’s letter. This was to Winthrop from Theophilus Eaton in Quinnipiac (later New Haven) dated 1 Jun 1640 and concerned the conduct of his brother Nathanael. A postscript at the end contained this passing reference to his “cozen Malbon”:

+++

+++

Malbon here may well have been the Richard Malbon who signed the Fundamental Agreement in 1639, but this postscript that Calder referred to was itself no evidence that Richard Malbon was part of the nucleus of a group that sailed from London on the Hector to establish a colony, as she claimed. All it proves is that Eaton had a cousin Malbon in New England in 1640, and that Eaton trusted him to do whatever was needed to rectify a situation.

+++

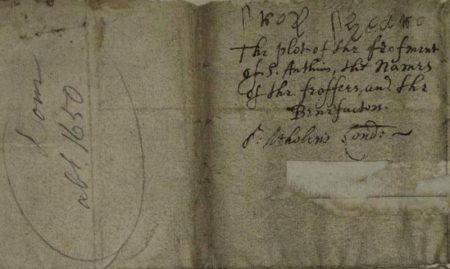

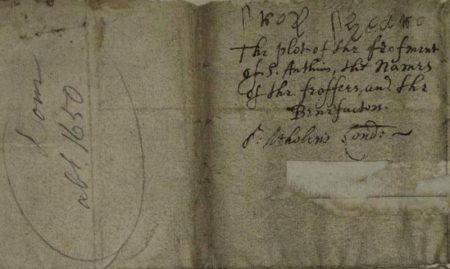

2. The Plot. Calder’s 2nd reference in this footnote 86 is to a summary in the English State Papers, Domestic of one part of a document comprising 3 folios concerning the parish of St Antholin’s and feeoffees. The 3 folios consist of 2 letters and a list of names. Calder’s reference was to the list of names but the document it is part of needs to be considered briefly as well.

+++

How the letters and list got into the State Papers is anyone’s guess as the St Antholins’ feeoffees were a subversive network working against the ecclesiastical authorities. The document was presumably seized at some stage, and the list was endorsed either then or later as “The plot of the feofment of S. Antholins, the names of the feoffees, and the Benefactors”. A date of “about 1650” was also added, perhaps by a later cataloger:

+++

The letters were undated but “1647?” is the suggested date at the top of the page in the State Papers where the document is summarised. Calder had discussed the St Antholins feeoffees earlier in Chapter 1, but hadn’t referenced this document in her discussion there. The letters and list were internal to the people in the feeoffees’ network and for them needed no explanatory context, so can seem enigmatic to outsiders, except the list which has an explanatory title.

+++

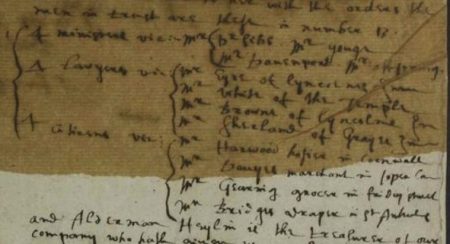

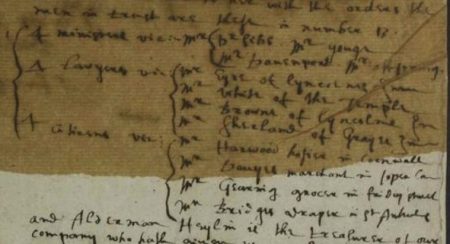

The Plot’s first letter was from Hugh Peters to Mr Vicars. It referred to donors, benefactors and gifts entered in a ledger. The snip of the first side below says:“The men in trust are these in number 13

4 ministers viz: [4 names (one Mr Dauenport)]

4 lawyers viz: [4 names]

and 4 citizens viz: [4 names]

and Alderman Heylin is the treasurer of our Company, and hath given us one impropriation, and we haue 5 or 6 already, so there is no miscarriage in the work”

+++

+++

Annexed to Peters’ letter is the Plot’s second letter—from a M Walley to Mr Vicars. It referred to receiving a letter from the feoffees but is altogether irrelevant to anyone called Malbon, which was the point of Calder’s footnote. It is superfluous to display an image of it.

+++

Also annexed to Peters’ letter is the Plot’s list of subscribers. This is what Calder referred to in this Footnote 86 of hers. It is entitled “A note of such gifts which have bin given and are yerely continued for the redemption of Impropriations and setling them upon godly and faithful ministers for time to come”.. It was summarized in the State Papers, Domestic as:

+++

For an image of the full page: click here.

Mr Malbone’s donation of £5 and comes about ⅔ of the way down the list:

+++

The Plot gives no further indication who Mr Malbone was, and no other name on the list matches another in Calder’s lists of names for her ‘group’.

+++

To be fair, Calder only said that Malbon was “perhaps” one of the subscribers to the company of feoffees for the purchase of impropriations, presumably acknowledging that the Mr Malbone in this list of donors may not have been the Malbon that Eaton mentioned as a cousin. The list’s suggested date of 1650 is curious with respect to Richard Malbon’s inclusion in her proposed 1637 emigration. But the word ‘perhaps’ in an argument begs further explanation. How reasonable a speculation is it? Without research, we the readers aren’t aware of this list of subscribers, but only of an opaque footnote to “State Papers, Domestic, Charles I, DXV, no.146i”. So we can’t judge.

+++

Furthermore, under the same ‘perhaps’ Calder added that Richard Malbon may have been a member of the Massachusetts Bay Company, see her full text above. The superscript footnote number 86 is actually appended to this part of the sentence, so the reader might well infer that one or other of the two items in the footnote provides evidence that he was a member of the Massachusetts Bay Company. But as we have seen in this discussion above, neither item in the footnote mentioned it.

+++

On the face of it, the footnote’s apparent scholarly citations carry persuasion. It’s only on investigation and analysis that it shows up to be specious. Calder’s method wasn’t a transparent way of trying to evidence a point.

+++

In conclusion, Calder’s footnote 86 is a complete red herring. Whether intentional or not, it was specious use of obscure references purporting to provide evidence. As for evidence that Richard Malbon was part of the nucleus of a ‘group’ in England that sailed on the Hector in 1637, the two references in the footnote are entirely irrelevant. They were merely isolated mentions of someone surnamed Malbon or Malbone in documents from a few years later than 1637, perhaps the same person, perhaps not:

1. Eaton’s letter simply referred to a Malbon in a postscript about something completely different.

2. The ‘Plot’ related to people associated with St Antholin’s and the company of feoffees for the purchase of impropriations, one of whom was a Mr Malbone, but it made no reference to the sailing of an emigrant group to New England. Of the people mentioned in it, Rev Davenport was the only name definitely common to the New Haven planters.

Calder’s footnote 86 is another good illustration of the extremely bad quality of the evidence she provided for her lists of passengers.

Footnote 87:

Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, 5th Series, I, 319-321.

Comment:

+Read more